Release the Killing Bar

I remember it was me who wanted to use the poison. As I recall, we were standing in the hardware super-store, my kid brother Paul and me, looking at a wall of fancy contraptions, powders and $6 gizmos guaranteed to catch mice alive, when my mother marched up the aisle, snatched four $.99 traps and huffed, “God-damnit! They all catch mice the same. Yuh gonna throw all my money away?”

That was my mother’s real beauty. However short-sighted or misguided her intentions were, there was always a sure-footedness to each and every step. I can still picture her in the bathroom of our small apartment preening her ruined hair and wrestling with foundation to soften any signs of real life. And with a few final pumps of hair spray, standing back to admire the new unevenness of her head, then grinning as if to remark, “Perfect.”

At some point during this 60-minute drill, Paul and I would end up in the hallway just outside the door, sitting on our heels, watching the coordinated dance of hands and hair: a round brush twisting under a blow dryer as her foot tapped out the time of the song on the stereo; the careful application of various gels and sprays in a very strict sequence; the eye shadows and eye liners; the make-up tackle box perched on the back of the toilet where I kept my comic books; the dressing room light bulbs; the hum of the exhaust fan as it slowly sucked out the smell of her perfume and carried it away to the apartment next door. All part of the plan, each and every step.

We’d ask her questions about the kind of nightlife we’d only seen pictures of on television. “Do you play pool?” Paul would ask. “Is the mafia there?” I wanted to know. Her answers were often too vague to satisfy our growing curiosity and I’d continue with my pointed line of questioning: who, what, why? Occasionally, she’d offer up something that would lodge itself in my brain, taking up enough space to make my mind turn to other things, like the Tuesday night television line-up or dinner that was sitting on the counter just waiting to be popped into the microwave. I’d even gone so far as to memorize dialogue from certain prime time dramas and would ask her about things like whiskey, suicide and college, to which she would scowl, then laugh as if she’d just gotten the punch line of some terrific joke. I imagined her standing in the center of a circle of admirers, smoking long cigarettes and blowing perfect rings that rose through the purple air, light and airy as all her aspirations. I thought of her floating from room to room in what I believed to be a magical kingdom where adults talked freely, and the questions became interesting, unlike the ones people typically found to ask a thirteen-year-old boy: about school, about basketball, girls and summer plans, about nothing. I was desperate to break the code of this new language, to laugh at the inside jokes and order another round of drinks.

It was cold for September. The three of us had just spent the summer negotiating the newness of our family situation, and while Paul still cried himself to sleep most nights, we were starting to have fun most days.

“What’s that?” my mother shouted into the phone, twisting the cord around her index finger. “Oh . . .I’ve known him for a few weeks. Down at McGilvery’s. But you know,” she hesitated, as if reconsidering something. “He knows Jessica. Oh God, you’ll just love him, Claire. He’s rich, too. Has a motorcycle and a house over by the forest.” She turned away and whispered something into the phone, then laughed nearly spilling her glass of wine. “Uh huh… yes.. Oh Jesus, Claire, you’ll meet him tonight. I told yuh, he’s bringing his friend. Can’t talk about it now, hon,” she said looking at Paul and me sitting on the sofa, glued to the TV. “Call yuh later.”

Neither my brother nor me really cared about how great he was, or what he owned, or who he knew. What did we care? He wouldn’t stick around anyway.

“Let’s go to the pond, Franklin,” Paul called out grabbing the little red jacket that was hanging on the shoulder of the chair where he’d left it when we came home from school. I grabbed our mitts from the table and picked up the bat.

“Damn-it boys, you better be back before I leave. I mean it.” Without looking up, I squeezed the old remote, which provoked a soft click, after which the image on the television popped, then disappeared, leaving behind the ghost of a dish detergent commercial, seemingly forever trapped in our little living room here in Michigan, so far away from the rest of the world. A fading signal, lost somewhere in the cracks of America.

Pop.

Paul and I headed out across the parking lot toward the pond, passing a nearby park with flat green fields full of kids playing soccer. Adults huddled together in bleachers with their hands in their pockets, their mouths breathing smoke.

Off in the distance, more than one siren could be heard moving up the street, creeping closer. I followed Paul towards the field where we sat down next to Mrs. Weaver, a woman we knew from school, who was studying the children’s little legs and feet as they kicked and chased after the tiny white ball.

“Hello Franklin. It’s nice to see you. How’s your mom? You guys adjusting to all this cold weather,” she said laboring the obvious in way that made me angry.

“Why don’t you crawl back to your nest, little rat,” I whispered into my mitt.

“Have you thought anymore about next weekend’s campout? You know it’d be good for you and your brother. Don’t worry about your mother. I can pick the two of you up and take you with me.”

Oh yeah? Screw you, I thought. “That’s okay Mrs. Weaver. Paul and I are going to my dad’s next weekend,” I lied. “Thanks anyway.”

Her eyes opened wide and she tilted her head just slightly. “Well, you’re always welcome to join us. Just let me know.”

I sighed, shimmying under the bleachers, dropping to the ground, where Mrs. Weaver had been reduced to a pair of folded legs. Paul and I weaved our way back through the support beams and sped to the far corner of the field before disappearing from view into the trailhead.

Walking shoulder to shoulder, we wormed our way deeper into the woods towards the little pond. I grabbed the neck of Paul’s sweatshirt and shoved him up the trail, before chasing after him again.

“Why are we running so fast, Franklin?” Paul squealed. “Quit it!”

“Keep running.”

We didn’t stop until we reached the bend in the trail where it opens up to the clearing surrounding the pond.

“I didn’t know we were going to dad’s this weekend,” Paul said searching the edge for frogs. “Is he really picking us up?”

“Nah, we’re not going anywhere stupid.”

“Then why’d you tell Mrs. Weaver we were . . .”

“You just don’t get it, do you?” Paul most certainly did NOT get it, I knew that. Although I was getting tired of letting him go on with this stupid charade. He was old enough to know better. A boy can only play pretend so long.

“You think he gives a shit about us?” I said picking up a frog and tossing it into the air. “Mom says he got married last weekend in Las Vegas. You know where that is?” I asked swinging my bat and making it rain frog guts. “A long way away from here, Shrimp. Toss me another one.”

“You’re lying,” Paul corrected, swallowing. “He wouldn’t do that without telling us first.”

“Really? When’s the last time you talked to him?” I egged him on knowing it was too much, but going after it anyway. “Mom told me not to tell you cuz she knew you’d be a baby about it all. Now you know, baby. Your turn. I’ll pitch.” Paul backed away slowly from the pond with an edge of scorn. I found the biggest frog I could find and underhanded it towards him before turning to outrun his bloody cut. He stepped into it, took a good swing, and missed entirely. Whiff. The frog disappeared into the tall grass behind Paul, while he collapsed in a twisted heap. Lucky frog, I thought.

“Let’s go.”

By the time Paul and I returned home, the apartment was already dark and smelled like bacon and buttered toast. I figured my mother had left her bedroom window open. The McPherson’s next door were always making breakfast, no matter what time of day it was. Our own dinner was waiting for us on the kitchen table: a frozen pizza and a can of parmesan cheese, which reminded me, we had a mouse to catch.

I dropped my coat on the floor, and walked towards the freezer door, nearly slipping on a little puddle of water in front of the refrigerator. “Piece of shit!” I could hear my mother saying.

Paul uncoiled his neck the way he did when he was nervous and ran screaming out of the kitchen towards the front door. “I SEE IT! FRANKLIN!QUICK! The MOUSE! FRANKLIN!”

And there it was. The mouse scurried along the far wall under the picture window. It was a lot smaller than I expected. Quicker, too, disappearing behind the television set.

I froze, unsure of what to do. Run? I glanced at Paul who was now perched on the arm of the sofa, with his arm extended in accusation of this darkened room, as if this whole mouse trapping business was just too much to believe. Racing back to the kitchen, I dumped the bag of traps onto the table and without much effort, managed to pop open the plastic clamshell, spilling its contents onto the linoleum floor: a boxy looking mouse trap, a set of instructions, a short metal pin, a piece of cardboard with colorful pictures. Without hesitating, I hoisted my foot into the air and snatched at the directions.

The card was no bigger than a stick of Big Red and included three illustrations depicting proper mouse trapping for this particular death machine. 1. Bait the plate. 2. Set the trap. 3. Release the killing bar.

Rifling through our meager supplies, I found everything I needed in the cupboard above the sink and carefully loaded its metal tongue with peanut butter and a handful of Fruity Pebbles.

“He’s behind the TV!” Paul shrieked.

“Shut up! You’re gonna scare him away.”

Moving quickly, I made my way — trap in hand — towards the television set where I spotted the mouse’s tail curled around the corner. I motioned for Paul to move to the other end of the sofa, as if the mouse could decipher the schemes of a 13-year-old boy. Paul wiggled his way across the afghan as quietly as he could.

“When I tell ya,” I whispered, “hit the lights.” The mouse’s tail didn’t move. Slowly, I placed the loaded trap on the floor, cocked the killing bar, and gently inched it towards the wall with the tips of my fingers, half expecting it to break my hand.

“Is he sti—” Paul squeaked.

“Shhhhh. The lights,” I said pointing towards our bedroom.

Paul and I tiptoed down the hall, and shut the door behind us. The room smelled like glue and paint. Paul sat insecurely on the corner of his bed, while I inspected the model Mustang we’d built last weekend. “We’ll give it an hour,” I said opening the Mustang’s engine hood and trunk lid to make sure the paint hadn’t sealed them shut.

“Franklin. Do you think we’ll—”

“Go to bed, Shrimp. It’s late. I’ll wake you up if I hear anything.”

“But I’m not tired. Besides, we’ve got to get that mouse.” Paul prodded his mattress that was sitting in the floor without a frame. “Otherwise, he’s liable to crawl in here with me.”

“You can sleep in my bed tonight if you want. I’ll take the floor. Listen,” my voice softened, “about Dad, I just thought you’d wanna know is all. It’s no big deal. I wouldn’t worry about it.”

“What?” Paul said, chewing on his cheek. “I’m not worried. I’m calling him tomorrow.”

“Hey, did you ever start that book I gave—”

THWACK!

The suddenness of the moment filled our tiny room like a flash flood; my chest expanded with a kind of wakefulness, leaving me with the feeling that I’d never grow old.

We peeked out the door, half expecting to find Big Foot lying in the hall, then slowly crept into the living room where we spotted the tripped trap, with just the end of the mouse’s tail visible.

My God, we’d actually done it!

Satisfied with the kill, we tidied up the mess of our mouse hunt before crawling into bed to wait for our mother to come home. It wouldn’t be long. I played it all out in my head: She’d stumble in some time after midnight and see the mouse we’d left for her on the kitchen table; then we’d listen for the doorknob in our little bedroom to rattle and shut our eyes as tight as we could anticipating the smell of her sweet breath to fill our lives once again.

I came across each thought and turned it over carefully, as if it wasn’t something ugly wrapped in fear and worry, but rather an opportunity printed on leaves from the tulip tree right outside our apartment. I stood on Paul’s pillow and cranked open the window, then lay back down and listened for the soft whirring of those little green leaves as they turned circles in the wind. Within minutes, I drifted south into a sea of blue water, circling in a small boat and hunting fish.

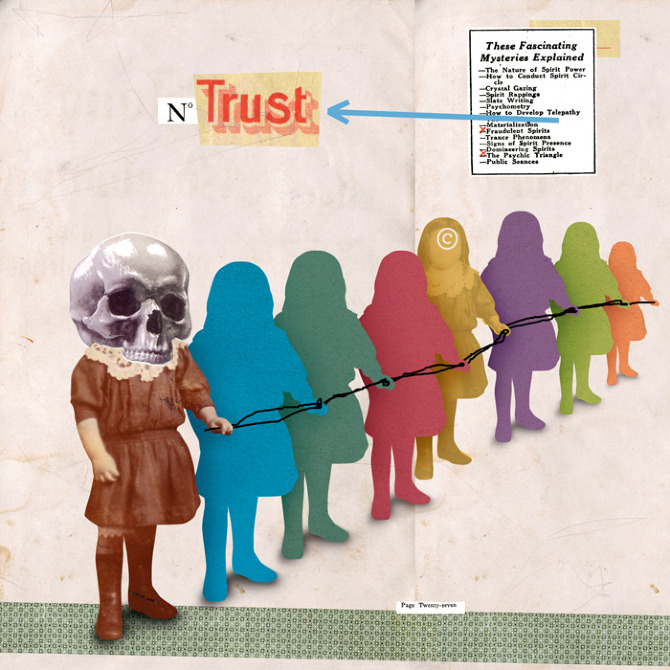

Illustration by Eric Stine

2 Responses

Add your comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

yes. more, please. please, sir. i want s’more.

I feel twelve. Great, intriguing beginning.