In Case You Don’t Drop by the Office, This Is What It Says

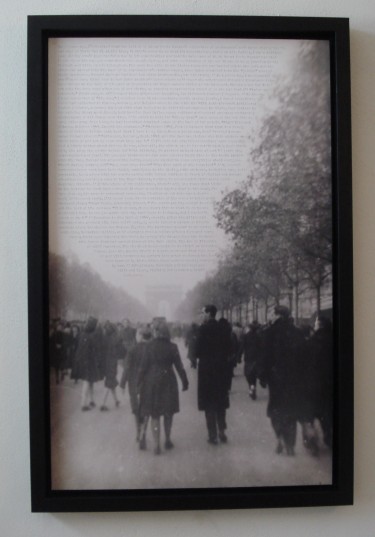

Many years ago, I inherited what was left of my Great Uncle Howard’s collection of photographs he’d taken during the final days of World War II. At the time, it didn’t occur to me that I’d inherited anything at all. Rather, I was a thirteen year-old boy who’d been handed a box by his grandmother and told to take care of it. My Great Uncle Howard had died in his sleep the way you read about some people dying, and with no children of his own it was up to my grandma to dig through and divvy up his belongings. She made two piles in his living room: one was hauled out to the curb and the other was packed into the back of my grandparents’ station wagon, then later unpacked into the “yellow” room of their farmhouse. Howard Jackman had been her older brother. She, his kid sister. // As a young boy, I accompanied my grandma on many trips over to her older brother’s house where we’d spend the afternoons throwing tomahawks into tree stumps at the back of his yard or inspecting old black-powder rifles in his basement. Steering her big Buick out onto the busy road after one of our visits, my grandma remarked how proud of me she was that I’d “taken an interest.” Truth was, we all enjoyed these afternoons together, for different reasons I suppose. // So the day I took possession of “the box,” I somehow knew it was something worth saving. Inside, I found everything my uncle had collected in France, Germany and Belgium when he was with the 45th Anti-Aircraft Artillery: woolen uniforms, a greasy bayonet with what looked to be dried blood staining its blade, love letters to his wife (my Great Aunt Jinny), belt buckles from fallen enemy soldiers and several packages containing photographs of all shapes and sizes. // In order to help his “Jinny-Dear” make sense of his new life so many miles away from home, he had inscribed detailed notes on the back of his prints. “Staff Sergeant DiBacco. Belgium 1945. Caught him unawares.” “Belgium 1945. Just so happens that that is a lovely piece of chicken (white meat too) that I have in my hand. Sure a tough war, huh? Wrecked German radar in background.” “Erlangen, Germany, Sept. 1945. Ask the Jackman sisters who this picture reminds them of and let me know what they say. H.” // I’m sure his playful commentary made everyone feel a little better about things. He was, after all, the oldest man in his outfit having been drafted by the Army six months before his 40th birthday. He arrived at boot camp almost 41 years old. His younger brothers-in-law were serving their time in the South Pacific with the Navy. Spread out around the world, everyone wanted to know everything about everyone. “How’s Harley getting on?” “Any news from Fred?” “Was Vern part of the invasion?” My uncle’s correspondence must have been doubly satisfying to the family, with pictures, including many self-portraits, to go along with his words: posing with fellow soldiers in front of shelled out German schoolhouses, smoking a pipe in the Black Forest, resting in un-occupied cafes along quiet Parisian streets. // In the whole of his collection, there’s only one image that hints at the horrors he must have endured. It shows a soldier laying dead in the road, his face shot up, his arms in a perpetual surrender. Whether or not this was a shockingly infrequent sight, I’ll never know. His description of the scene is brief and stripped clean: “Dead Negro. Evidently French.” The words are big enough to crowd out the rest of the message: “This is war, Jinny-Dear; this is what we do to one another; I hope to see you again some day back home in Indiana, but I wouldn’t count on it. H.” // Sometime in the fall of 1944 shortly after the allied forces had liberated the ancient city from evil’s grip, my uncle joined a parade of French patriots along the Avenue des Champs-Élysées. The Parisians appear to be moving with slow, tentative strides, as if emerging from a cellar after a long and scary storm; their eyes scanning the scene to survey the damage from the destructive forces that had passed through the dark night. The Arc de Triumph was still standing. The chestnut trees continued to clutch at twisting leaves. Even the Avenue itself was a wide reminder that life goes on and will continue to persist long after we forget the lessons learned by those whose lives were so wholly changed by war. // It’s already December and the boys are still out there, fighting for something that’s long gone.

One Response

Add your comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This was great. I come from a long line of men who were called away to war. My older brother is in Iraq right now. I have a few trinkets from my grandfather, my father, and a bayonet my brother brought back from his first tour. They’re sobering reminders of the histories our families helped to create.