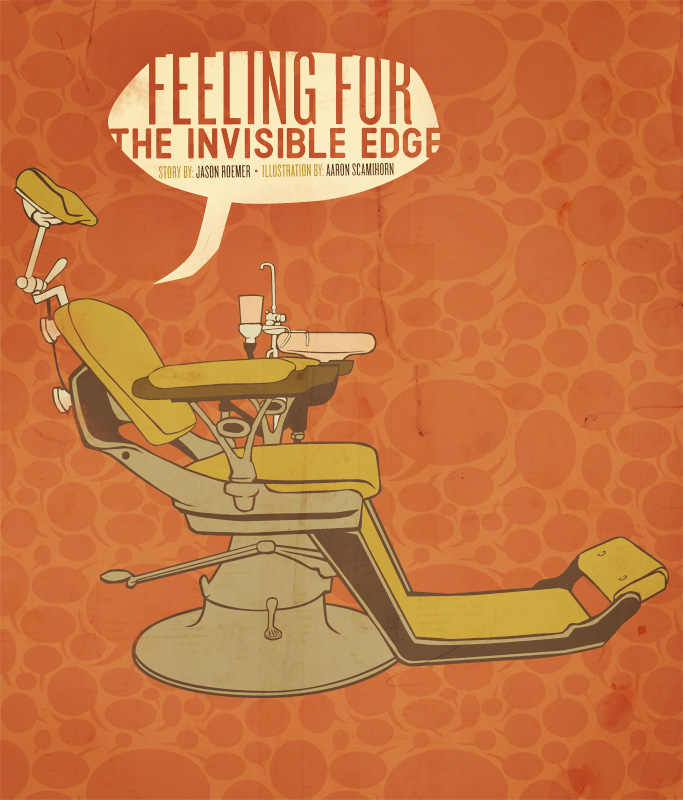

Feeling for the Invisible Edge

Words by Jason Roemer Illustration by Aaron Scamihorn

http://frcio.us/3aX5

http://frcio.us/3aX5

As a dental hygienist, my wife comes home covered with strange stories about the things people say when they’re stuck in a chair. Mostly, it’s anecdotal evidence of the three Ds: Divorce, Disease and Dough. I listen intently, nodding my nose in anticipation of the good parts (it’s crazy what people will share with strangers). Occasionally, she’ll begin in such a way that makes me sit a little taller, knowing we’re in for a huskier evening of dinner-talk. Last night was one of those days. Staring at a bowl of Buckshot Gumbo, she put down her spoon, carefully turned the napkin over in her lap and asked me if I wanted to hear a weird story about her day. You could have planted peas in the creases of my forehead. It was obvious: things were about to get interesting.

8:17 am // “THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN CROWN.”

“At eight this morning,” my wife (let’s call her Robyn) began, “the lab called to tell us Greg’s crown was ready. Greg’s a funny guy. 55 years old, drives a bus. Anyway, Dr. Dentist said he’d pick it up this afternoon.

Ten minutes later, the phone rang again. It was Greg’s son calling to tell us Greg had been killed by a truck on Sunday evening.”

A thin layer of oil began to swim on the surface of our gumbo as Robyn continued. “Dr. Dentist asked if he’d like to come by some time and get his father’s gold crown. Greg had died with one of our temporaries in his mouth,” she clarified for my sake.

“What did he say?” I asked racing a piece of shrimp around the edge of the bowl. “I mean, is that a weird thing to ask?”

Despite the obvious awkwardness of the pending exchange, Robyn explained there was really no other way around it. “It’s his. He already paid for it — the lab isn’t going to refund the money for a gold crown. And, of course, we can’t keep it.”

“I guess not, no. I just never thought it about it is all.”

Watching Robyn’s neck run red, it struck me how intimate a temporary crown could make a situation like this — intimate and incomplete in a way that can only make your life seem one or two steps closer to some invisible edge.

Our conversation tacked across the obvious until we found ourselves inside something new again, imagining Greg’s son coming to the office to retrieve his father’s tooth, what they’d say, and what he’d do with the damn thing once he got it home.

Where do you store the old man’s molar, anyway?

“It’s gold,” Robyn replied holding her chin. “He could melt it down and sell it if he—”

“I bet he doesn’t show,” I interrupted. “I wouldn’t.”

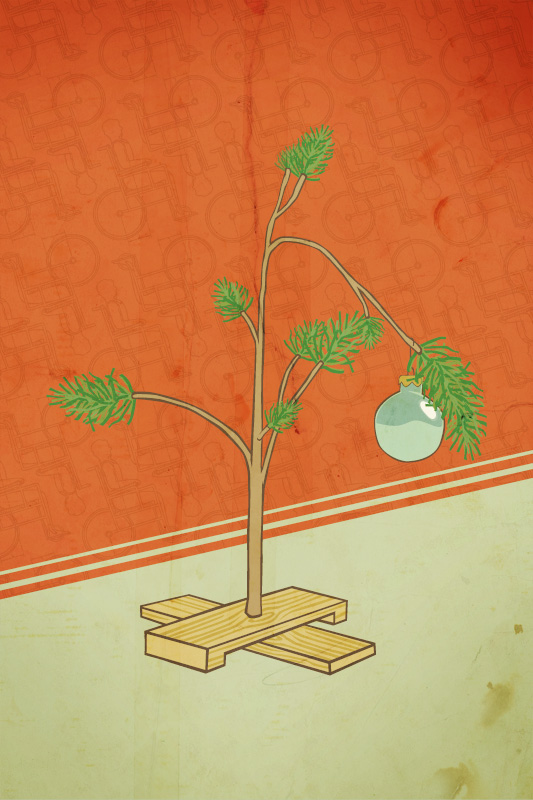

11:30 am // “WHILE VISIONS OF SUGAR PLUMS DANCED IN THEIR HEADS.”“Just before lunch,” Robyn continued. “We saw the mother of the super-smart family I’m always telling you about.”

I knew instantly to whom she was referring; The Family had been the topic of many dinner-talks in the past. Like the night I grilled salmon and learned about how their 19-year daughter had dropped out of Duke’s Biomedical Engineering master’s program because she didn’t feel challenged by the coursework despite being five years younger than everyone in her classes. Or the weekend I broke out the tajine to roast a lamb shank and listened to Robyn tell me about how the husband comes home from work every night and takes his blind neighbor running with him, rain or shine. Or the day we had breakfast for dinner and Robyn told me about a devastating letter the office had received from the mother of this Glass-ian clan, explaining how the 23-year-old son— the one with cerebral palsy — had died in his sleep waiting for Christmas morning to arrive.

Imagine that.

“I haven’t seen mom since . . . it . . . happened,” Robyn said, “so when I went out to the lobby to bring her back for her eleven o’clock, I already had the x-ray jacket in my hands knowing I wouldn’t be able to hold it in once I saw her. I thought if I could just get her back to the x-ray room quickly, I’d make it. As soon as I saw her, we both just burst into tears.”

The mother told Robyn how hard the past few months had been. About how on Christmas morning, when The Family found him in his bed, the police had to be called to investigate since it was a home death. The mother went on about how the cops spent the morning digging around his room and looking in the basement for something they never found.

While neighbors were busy exchanging gifts and swiping stories, The Family was quietly trying to re-assemble the puzzle of their life that was broken by a young man who couldn’t lift a finger — who just laid in his bed next to a tiny Christmas tree he’d decorated himself.

“I’ve been volunteering for the past month,” the mother told Robyn, “just to stay out of the house. When I’m at home, I have this strange feeling like I’m waiting for someone to come through the front door any minute. Hours can go by. You knew him. He wouldn’t have wanted me to just sit around and rot. We were always going places together. Running errands, shopping.”

Robyn pushed her bowl to the corner of her placemat and told me about the last time she had seen the son alive. It was November. The mother had scheduled a cleaning for all five kids — blocked out the whole afternoon. At one o’clock sharp, The Family’s white van pulled up. One by one, they filed out before the mother leaned in and hefted her oldest son onto her thick shoulders, then carried him up the short flight of steps and into the office where she plopped him down onto one of the sofas in front of Judge Judy.

“She was always picking him up and getting him out of the house. It’s hard to imagine,” Robyn added, “how lost she’ll be with no one to carry.”

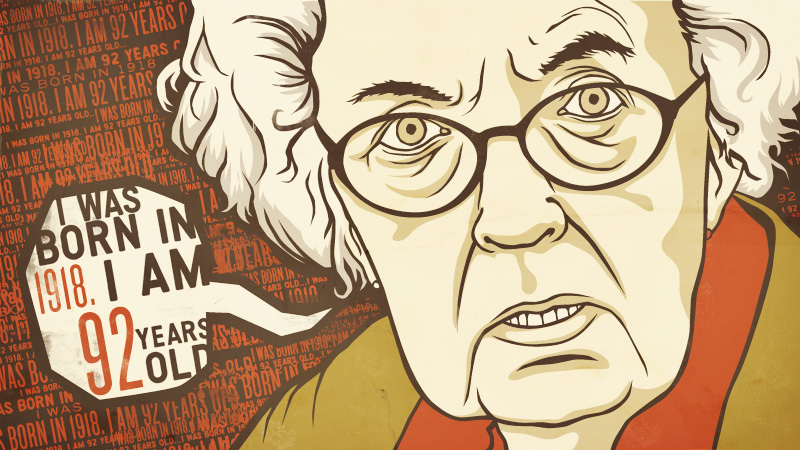

4:00 pm // “JUST START AT THE BEGINNING AND TELL ME EVERYTHING.”“Our last patient of the day was a 92-year-old woman who still has all of her teeth—”

“Seriously?!”

“—she’s really sharp. Always talking about food. At least she used to.”

Passing me bread wrapped in an orange napkin, Robyn explained that the woman’s husband had suffered a stroke last November. Before the ambulance ever made it to the house, he was gone. That was six months ago. The nonagenarian widow — who’d been chauffeured to her appointment today by her son who was wearing a camouflage t-shirt that stretched tight across his belly and said “HOOKED ON QUACK” — was merely a shadow of her formal self.

Once the widow was seated in the chair, she sad she wasn’t sure how old she was. Looking at the chart, Robyn said, “Let’s see, it says here you were born in 1918. That means you’re 92 years old.”

The widow looked up with watery, glassy eyes and slowly repeated what she’d heard, “I was born, in 1918. I am 92 years old.”

Moments later, when the dental assistant popped in to say hi, the widow repeated it again, “I was born, in 1918. I am 92 years old.”

At the end of the appointment, Dr. Dentist came in and gently patted her on the arm, telling her how good it was to see her again. The widow lifted her left shoulder off the chair just enough to get a better look at the doctor and quietly whispered, “I was born, in 1918. I am 92 years old. I was born…in 1918.”

10:15 pm // “INCH BY INCH.”Gathering up the plates and piling everything onto one placemat, Robyn pushed her chair away from the table and shot a giant hole in the conversation by announcing that she didn’t want to grow old, how she’d rather die young. I blew out the remaining candles, then followed her into the kitchen, where I poured myself a tall glass of milk. Together, we headed upstairs to watch a few minutes of TV before going to bed, feeling around for some sign of that invisible edge.

Illustrations by Aaron Scamihorn

5 Responses

Add your comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Amazing.

These illustrations are fantastic.

Really enjoyed reading this. And seeing Aaron’s illustrations. Great work.

I want more, more, more! And how exactly does a blind person run? Lots of trust I suppose?

Jason, you are the mad genius of your household, dancing naked before the mirror…or something. Nice work.